A growing number of experts warn that food fraud is quietly draining up to $50 billion from the global food industry each year. It can also put consumers at risk of serious illness.

According to industry insiders, blockchain technology could help stop counterfeit and adulterated products. Yet rolling out such systems across complex supply chains will demand big investments and careful planning.

Food Fraud Hits Hard

Food fraud means tricking buyers about what’s in their food. It can be as simple as mixing cheap oils into olive oil or as dangerous as putting melamine in milk. Based on reports, a 2008 milk scandal in China sickened over 300,000 infants.

As defined by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, food fraud is the deliberate act of misleading consumers about the true quality or contents of the food they purchase.

Food fraud may only be a small slice of a $12 trillion sector, but it is the same size as the economy of a country like Malta. Buyers lose trust and brands suffer. Even honest farms and shops pay the price when fraud scandals break.

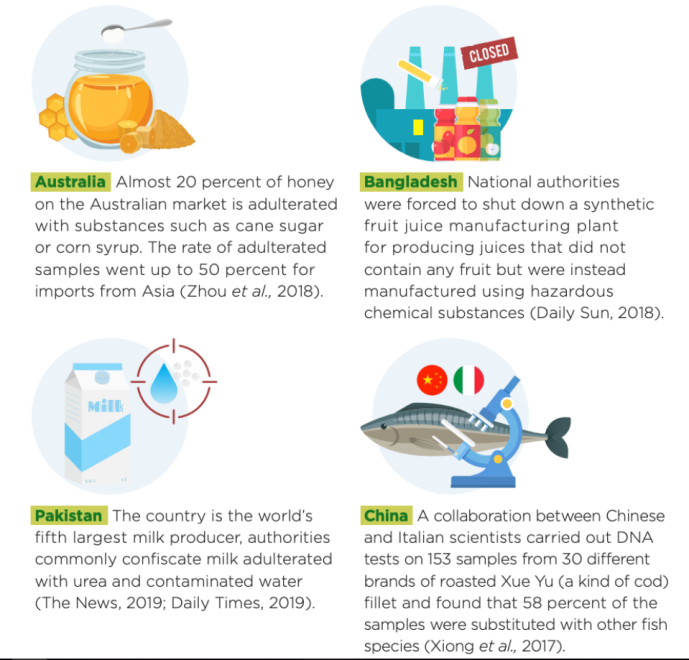

Recent cases of food fraud that recorded across Asia and the Pacific. Source: FAO

Blockchain Offers Transparency

Blockchain works like a public ledger. Every step in the supply chain can be recorded and locked in. According to Walmart, using Hyperledger Fabric to trace pork in China and mangoes in the US cut tracking times from days to seconds. That means if bad meat moves down the line, it shows up almost immediately.

Once data is on the chain, no one can delete or change it. This gives buyers and inspectors a clear record from farm to fork. Tech leaders say this kind of open system can scare off fraudsters who thrive on secrecy.

According to authorities, food fraud is the intentional practice of misrepresenting what’s in a food product—whether by adding cheaper ingredients, swapping in lower-quality items, or lying on labels—to trick consumers and make extra money. Image: Gemini.

Cost And Complexity Stand Firm

Even so, using blockchain is not cheap or simple. Companies must pay for software, hardware, and training. They also need sensors that feed data into the chain. If those devices break or lie, the ledger will have bad data.

Oracles that link real-world events to blockchain can be hacked. Some businesses worry about sharing too many details with rivals. Regulations are still vague in many places.

Getting everyone—from farmers to shippers to grocers—on the same page will take time and cash. Based on estimates, setting up a large system could run into the millions of dollars for big players.

Steps Toward Wider Use

Industry groups and firms like TE-Food and Provenance are rolling out pilot projects. They bring together farmers, distributors, and retailers to test blockchain networks. Training sessions are under way.

Some governments in the EU and Asia are talking about clear rules for food traceability. Experts say that starting small, with one product line or region, will show value faster. Once a few success stories emerge, more companies might join.

The Road Ahead

Food fraud is not going away. The tools to fight it are real but costly. Blockchain could end the crisis if it is used right. That means fixing gaps in cold-chain tracking, solving data islands, and getting clear rules from regulators.

It also means spending on good sensors, secure oracles, and strong partnerships. If those pieces fall into place, blockchain will stop many fraud cases. Until then, the battle to protect food and buyers will remain steep.

Featured image from SafeFood, chart from TradingView

Editorial Process for bitcoinist is centered on delivering thoroughly researched, accurate, and unbiased content. We uphold strict sourcing standards, and each page undergoes diligent review by our team of top technology experts and seasoned editors. This process ensures the integrity, relevance, and value of our content for our readers.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  XRP

XRP  USDC

USDC  Wrapped SOL

Wrapped SOL  JUSD

JUSD  TRON

TRON  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  Figure Heloc

Figure Heloc  Cardano

Cardano  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  USDS

USDS  Binance Bridged USDT (BNB Smart Chain)

Binance Bridged USDT (BNB Smart Chain)  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  LEO Token

LEO Token  Monero

Monero  Chainlink

Chainlink  Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid  Coinbase Wrapped BTC

Coinbase Wrapped BTC  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  Canton

Canton  Stellar

Stellar  WETH

WETH  Zcash

Zcash  USD1

USD1  Litecoin

Litecoin  Sui

Sui  Avalanche

Avalanche  USDT0

USDT0  Dai

Dai  sUSDS

sUSDS  Hedera

Hedera  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  World Liberty Financial

World Liberty Financial  Ethena Staked USDe

Ethena Staked USDe  PayPal USD

PayPal USD  Toncoin

Toncoin  Cronos

Cronos  Rain

Rain  Polkadot

Polkadot  Tether Gold

Tether Gold  Uniswap

Uniswap  MemeCore

MemeCore